Why you DON’T Need Orthopedic Surgery for Joint Pain

There are often other, more effective, less invasive and risky solutions for treating joint pain and reclaiming your mobility and life. Let’s start with functional training.

Table of Contents

- My History with Orthopedic Surgery Recommendations

- With Joint Pain, Correlation Doesn’t Equal Causation

- Orthopedic Surgeries are NOT Based in Fact

- How Orthopedic Surgery Results are Reported

- Why Orthopedic Surgeries Continue, Despite the Evidence That We Don’t Need Them

- How Insurance Companies Contribute to the Problem

- The Risk of Drug Addiction with Orthopedic Surgery

- Orthopedic Surgeons Still Have a Monopoly on Joint Pain

- How to Fix Your Joint Pain Without Orthopedic Surgery

- Closing Thoughts on Orthopedic Surgery for Joint Pain

The man in front of me fumbles for his wallet at the credit card terminal.

He looks about sixty with a grimace and belly that add another ten years. His shiny black cane clatters to the floor. I start to move to help. His otherwise attentive adult son doesn't move to help. I decide against stepping forward for fear it might feel patronizing.

The man's hand is inches from the cane, but it takes him several more seconds to grab it. He grinds and groans as he stands back up.

"Damn it," he mutters as he stands as fully upright as he can. His hand goes to his right hip.

The cashier is a cheerful guy who appears to also be in his sixties. "Hip pain?" he asks.

"Aw, god, yeah. But it's this damn knee I'm worried about." He points at his right knee. It's wrapped in a thin black brace. "I had it replaced a couple years ago, and I'm worried the damn thing is giving out already."

"You might have to get that hip done too, huh!" the cashier says.

"Ha!" The man scribbles his signature on the screen. "I ALREADY had this hip replaced. Still hurts. Hell, I had my back done, my shoulder done, this hip, and this damn knee."

He starts putting his wallet away. "I'm supposed to have this other hip done, but I ain't doing that one 'til I'm dead."

He laughs and shakes his head. He pivots slowly toward the exit. "I'm putting that off as long as damn possible. I told my doctor he can cut on me all he wants when I'm dead. Ha!"

The cashier laughs. The adult son carries the bags.

The man limps out the exit. The outlines of his bony shoulders poke stiffly against his shirt. His skinny legs shake with each step. The cane wobbles with every strike.

This was a true story.

I share it because it’s a reminder that in the majority of cases, invasive, expensive surgery isn’t necessary. It doesn’t produce better results than alternatives like identifying and improving upon muscle dysfunction.

Maybe you can relate if you've got chronic or recurring joint pain. Maybe your doctor tells you that the only solution is surgery. He or she points to some X-rays and MRIs and says, "This thing right here is what's causing your pain. All you need to do is replace it, and you'll be good as new!"

Is it time to replace this man’s hip, knee, and shoulder joints? Which would yield more strength and confidence: six months dedicated to functional training or six months spent in bed recuperating from multiple surgeries? Image courtesy of Miikka Luotio

My History with Orthopedic Surgery

I've been studying the human body and fixing my own chronic pain, without invasive surgery, since 2007.

When I first started, I was unable to walk more than a few blocks without pain. I couldn't walk down stairs without a sharp pinching in one of my knees. My back, wrists, hands, feet, hips, and one shoulder were buzzing with pain all the time.

I was reluctant to try surgery to fix any of it, even though my pain and discomfort was bad. I had seen multiple friends undergo shoulder surgery to fix their shoulder problems. One friend had one surgery to fix shoulder instability. He underwent another four shoulder revision surgeries. None were successful. The other friend had only one shoulder surgery. He showed me how he had lost over 90 degrees of rotation in his shoulder. His surgeon told him this was completely normal and permanent.

Surgery just seemed like a terrible option.

So I soldiered on, and I eventually fixed my chronic pain issues and got my life back. It took years and a lot of stubbornness.

When I started helping others, I was afraid to rock the boat too much. I was afraid that telling people surgery wasn't the right answer was overstepping a boundary.

But by now, I've spent a lot of time researching orthopedic surgeries and procedures, and I feel a lot more comfortable saying orthopedic surgeries should be the absolute last thing you try to fix joint pain.

Instead, it's best to spend at least a year revamping your entire life so you can retrain muscles properly before you seriously consider any orthopedic surgery.

This recommendation actually originally came from Dr. David Hanscom—a spinal surgeon who actively dissuades people from spinal surgeries. In his book Back in Control: A Surgeon’s Roadmap Out of Chronic Pain, he writes that having seen the dismal results of spinal surgeries and how much better people can get by focusing on muscles, he's become a strong proponent of a non-surgical approach to spinal issues.

I believe that same sentiment should apply to ALL kinds of joint pain.

In this article, I'll explain why. I’ll cover the reasons why you shouldn't be quick to trust orthopedic surgeries to fix your aches and pains. I'll cover key issues in the development of orthopedic joint pain theories, and I'll discuss the actual results from orthopedic surgeries.

See also: Your Joint Pain May Actually be Muscle Pain

With Joint Pain, Correlation Doesn’t Equal Causation

When someone with chronic pain comes to an orthopedic surgeon, that surgeon often points to X-rays and MRIs to show that labrum tears, meniscus tears, and bone shapes are all associated with the patient’s pain.

But what you see in the images—the alleged deformities and damage—may not be the cause of the pain. Correlation does not equal causation.

When you say something is associated, which is another word for correlated, with another thing, you’re saying that there is some kind of relationship, though not necessarily a causal (cause-effect) relationship.

For example, I might notice that whenever I sit in the backyard for two hours, my legs itch. Backyard sitting time is correlated with itchiness.

But is sitting in the backyard the cause of my itchiness? I can't say that yet. I'd have to do a lot more investigating to figure that out. Maybe I’d find that there are bugs in the backyard. I might notice that in the summer, there are more bugs and that seems to be when I am more itchy.

The number of bugs is associated with my itchiness. But do I have 100 percent proof yet that the bugs are the cause? No.

Once I observe that the bugs are landing on me and that I have little red spots where they were, I’m pretty darn sure that the bugs are the CAUSE of my itchiness! I know that there are more bugs in the summer, when I itch most after sitting outside. I know that bugs bite. I can see the immediate effects of these bugs landing on my skin.

With this preponderance of evidence, I can strongly argue that the association between the bugs and my itchiness is a causal relationship.

This blood sucker is associated with a lot of physical and mental irritation.

Sitting in my backyard is associated with itchiness. It isn't the actual cause of itchiness. The bugs are associated with my itchiness. And their bites are the cause of my itchiness.

In the case of orthopedics, labrum tears, arthritis, and other abnormalities are the justification for recommending and performing invasive surgeries, but they are usually not the cause.

The process of popularizing these surgeries is downright illogical.

It would also be funny if it didn't come with the risk of death or infection. In a 2013 study of in-hospital infections after total joint arthroplasty, published in the journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, rates of pneumonia, UTI, SSI, sepsis, and severe sepsis were all less than one percent, but the occurrence of pneumonia, sepsis, and severe sepsis increased the risk of mortality 5-66 times. Infection can have serious consequences.

See also: Is surgery a guarantee of improvement for FAI?

Orthopedic Surgeries are NOT Based in Fact

Surgeons see an association and they then invent and perfect surgical procedures to "fix" the alleged cause of pain or dysfunction.

Imagine this scenario: A short-sighted and blond-haired surgeon practicing in Tokyo notices that he has a lot of patients with chronic headaches.

He notes that all of these headache-sufferers have black hair. In fact, 100 percent of his patients with chronic headaches have black hair.

Based on this association, he believes having black hair is the cause of the headaches and that the way to correct the headaches is to change the color of his patients' hair.

His first attempts at using bleach to change hair color fail, so he gets more drastic.

He perfects a technique in which he removes his patients' skull caps and replaces them with donor skull caps from deceased blond-haired Swedes. He performs this surgery on 100 patients.

He creates a questionnaire for patients to report their results. Based on his questionnaire, a majority of his patients report 10-50 percent improvement in their headache symptoms! He writes a paper claiming 75% of his patients report moderate to strong improvement.

Their headaches are less frequent and less intense. There are no severe complications within three months following the surgery for any of his patients.

His paper is met with great fanfare! A 50 percent improvement is surely a miracle for headache-sufferers!

Now let's ask some important questions.

Does his paper prove that headaches are in fact caused by black hair?

No. The association between black hair and headaches in this situation deserves more investigation. Far more investigation. Because you and I live in the real world and have observed real life long enough, we know this is a dubious claim.

Does the fact that 75 percent of his patients reported a 10-50 percent improvement in their headache symptoms prove that the headaches are caused by black hair?

No. It proves that the procedure itself may affect the severity or intensity of headaches, but we don't know why. The outcome here does not prove the theory.

We also don't know if the way the questionnaire was worded or the way in which it was administered affected the reported outcomes.

For example, was the surgeon or one of his nurse's verbally asking the patients about the outcomes post surgery? Was there intended or unintended social pressure that caused patients to report better results than they actually experienced? Was the questionnaire itself asking the right questions and scoring things in a way that accurately reflected a patient’s experience and satisfaction?

Lastly, how badly did patients want to believe the surgery would work? Some might call this the placebo effect, and the placebo effect can be very strong. Read The New York Times’ coverage of placebo surgeries: The Placebo Effect Doesn’t Apply Just to Pills. Or watch this BBC documentary on placebo surgery:

In the end, the ridiculous story of skull surgery for headache relief is a story about a surgeon who had a theory based on association and invented a procedure based on that theory. This skull surgery may seem outrageous, but it reflects the same process by which new orthopedic surgeries arise—via observations of associations.

See also: How Shifting Your Perspective on Chronic Pain Can Help You Heal

I think I’ll keep my headaches and my skull, thanks. Image courtesy of Sammy Williams

How Orthopedic Surgery Results are Reported

In the above example, the surgeon published a paper with his results—a 10- to 50-percent improvement in headache symptoms post surgery. But we’ve seen how these results could have been due to a biased survey or survey methods, the placebo effect, or other factors.

To truly determine if his theory about black hair was right, and if surgery had better results than non-surgical interventions, the surgeon would have had to test it more methodically and scientifically, comparing patients who received the real surgery with those receiving fake, or placebo, surgery and other forms of treatment, including functional movement training to correct muscle imbalances.

Surgeons often initially report spectacular outcomes and zero complications, but they are also often reporting on limited case studies with an extremely high risk of bias. In short, initial results are often exaggerated.

It is only later, after decades of data on surgery results, that studies show poor outcomes and higher complication rates, including sometimes catastrophic infection rates, poisoning due to implant material, and the regression of progress within two years after surgery.

Sometimes negative results emerge. In one study, published in the Iowa Orthopaedic Journal, of 785 patients who underwent hip arthroscopy, the overall failure rate for primary hip arthroscopy with a minimum of one-year clinical follow-up was 18 percent. It was 10 percent for revision hip arthroscopy.

You can see this whole process clearly—in real life—when you follow the story of knee meniscus surgeries.

Knee meniscus surgery was invented to try to help relieve knee pain in the elderly. Then enterprising and well-intentioned surgeons thought meniscus surgery could save knees in younger athletes, too. The surgery ballooned in popularity for decades as a preventive cure for knee arthritis.

But in the last 20 years, study after study has shown three things about knee surgeries:

1) Knee meniscus tears are not a cause of knee pain.

2) Real knee meniscus surgeries are no better than placebo surgeries when it comes to reducing pain and increasing mobility.

3) Knee meniscus surgeries pose greater risks to the health of the knee (and the patient) than no surgery.

Still, the knee surgeries continue, despite strong evidence that they are not necessary.

In fact, knee meniscus surgery to repair and replace the meniscus is one the most prevalent orthopedic surgeries in the U.S. at the time of writing.

When first popularized in the U.S., knee meniscus surgeries were touted as being highly effective. Even today, you find websites claiming knee meniscus surgeries are 84-94 percent effective.

That's despite recent research that shows knee meniscus surgeries are no better than placebo surgeries. Both have efficacy rates in the 40 percent range.

In a 2018 study, published in the Annals of Rheumatic Diseases, researchers determined that several meta-analyses based on randomised controlled trials have failed to show a benefit of arthroscopic partial meniscectomy on knees over conservative treatment or placebo surgery.

The exact same pattern has happened with spinal surgeries, shoulder impingement surgeries, rotator cuff surgeries, and now hip impingement surgeries.

The history of back pain treatments also demonstrates the issues clearly. Over the last 60 years, the medical approach to back pain changes inch by painstaking inch.

It's taken a long time, but research has shown that back surgeries like spinal fusions are ineffective, costly, and risky.

See also: How Shifting Your Perspective on Chronic Pain Can Help You Heal

However, you will still find ads and exhortations in airline magazines and newspapers, and on reputable online medical websites to get your spine operated on. Why? Because surgery has been the default choice for decades and medical education, insurance-industry incentives, and practices still haven't caught up to the science.

(For a more in-depth look at the back pain industry, check out Crooked: Outwitting the Back Pain Industry and Getting on the Road to Recovery by Cathryn Jakobson Ramin.)

The bias to "fix" things surgically doesn't stop at just bones. Surgeons will even "release" (i.e. cut) muscles to allegedly fix a problem.

If a patient has hip pain and snapping for example, some surgeons recommend cutting the tensor fascia lata to fix the pain.

This has no logical or scientific basis. Severing a muscle's connection might somehow remove the pain and discomfort, but it will cause a loss of function.

So long as the metric is "pain relief at the original site of complaint," the surgery might appear to work in the short run. However the loss of function and the long-term negative effects aren't known or examined in the research literature. The predictable side effects will be muscle soreness, long-term changes in gait, and an inability to perform movements like hip flexion and hip rotation without compensation from other muscles.

I’m sure there is no ill-intent here. Orthopedic surgery was birthed on Civil War battlefields to save lives.

It made sense in that context: Get into the body. Get the thing out. Stop the bleeding. Fix the break. Get the patient stable and out. The intention in orthopedics is to heal, but it’s built on a philosophical foundation that strongly blames structural damage and deformity for pain, which we now know isn’t the true cause of pain much of the time.

See also: Hip Labral Tears: What You Need to Know and What Your Doctor Won’t Tell You

What else do we think needs to be taken out? Image courtesy of Piron Guillaume

Why Orthopedic Surgeries Continue, Despite the Evidence That We Don’t Need Them

Now, you might be saying, "Surely if a procedure is shown to be ineffective, hospitals and doctors would stop using it immediately!"

Large-scale change takes time. The entire world has been indoctrinated to believe that knee meniscus surgeries solve knee pain. Changing that perception in the minds of doctors will take decades. Changing that perception in the minds of patients suffering from knee pain will take more than decades.

In the meantime, patients will keep pushing for a surgery that they've been led to believe is effective.

Doctors and hospitals can try to push back on that a little bit, but patients who want a procedure they perceive is effective will search for a surgeon who will operate.

Surgeons who have been trained to believe surgeries help, and who get paid well to perform those surgeries, will continue to do the surgeries. The beliefs and incentive structure mean massive change in the surgical world may never come.

You might think that wanting to provide only the best and most effective treatments would drive change at hospitals. I believed this, too, for a long while. However, U.S. hospitals rely heavily on elective procedures to fund their operations and make a profit. For hospitals, up to 80 percent of their revenue comes from high-cost elective procedures like orthopedic and heart surgeries.

Even in government-run health systems, like the UK's National Health Service, these elective procedures generate revenue for hospitals, in a roundabout way.

Hospitals that wish to stay financially solvent are not going to push hard against unnecessary orthopedic surgeries when they rely on these big-ticket procedures to keep the lights on and profits coming. It's not wise to kill the goose that lays the golden eggs.

See also: PRP Injections–Are They Worth it for Hip, Knee, or Shoulder Pain?

Financial incentives make orthopedic surgery for joint pain a seemingly unstoppable juggernaut.

How Insurance Companies Contribute to the Problem

Now you may be thinking, "Well, surely insurance companies must push back against these types of procedures! Why would they pay if they don't work?"

For private insurance companies, the answer is that there is actually no incentive to push back. In the U.S., insurance companies make a profit by paying out less than they take in. By law, they must spend a certain ratio relative to the premiums they get paid. For example, insurers selling large group coverage may have to spend 85 percent of their premiums on medical claims and quality improvements for their customers. The rest goes to administrative costs and profit.

So let's run a simplified thought experiment.

Say you’re the head of one of these insurance companies. Last year your company had $6.66 billion in revenue. By law, 85 percent went toward medical claims and services for your customers. That left you with 15 percent, or $1 billion, for administrative costs and profit.

Now, you want your company's revenue to grow this year and next. What would lead to increased revenue for your company?

Increased premiums.

But how would you justify increased premiums?

The simple answer is increased medical claim payouts. You keep paying out a little more in medical claims every year. To be clear, this doesn't mean you just wildly approve every medical claim. You still want to have hurdles that infuriate and irritate your individual customers (😁 sorry, hard not to work that in as someone who's had and heard about some terrible experiences with American health insurance). But you’re happy to pay for some expensive procedures that gradually inflate your medical claim costs so that you can increase premiums with each successive year.

If the amount your company pays in medical claims goes up every year, your 15 percent cut keeps going up. With a few years of gradual increases, you could see your premium revenue reach $7 billion! And 15 percent of $7 billion is greater than 15 percent of $6.66 billion (by roughly $50 million)!

Whether the medical claims are for prescription drugs or orthopedic procedures, it doesn't really matter—as long as you don't suddenly start paying for a wildly expensive new procedure that a lot of patients might want.

You may have heard stories of insurance companies denying cutting edge treatments that cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. Paying for even a handful of untested, super expensive treatments would quickly eat into the bottom line.

On the other hand, a predictably increasing number of knee meniscus surgeries or spinal fusions every year just adds to your bottom line because you can gradually ratchet up premiums to stay in line with your increasing medical claims payouts.

So while we might think insurance companies have armies of scientists and experts combing through medical journals to make sure they're only paying for good treatments for their members, the reality is that the financial incentives actually lead in the other direction.

See also: Why Good Health is Countercultural

Talk with enough people who have undergone orthopedic surgeries, and you'll hear a common story.

The surgeon repairs the "damaged" structure, but the patient still has the same pain and discomfort months later.

The surgeon says, "Well, the surgery was a success. But maybe you need a second surgery because we might've missed something or we need to remove scar tissue." (Listen to the Dose of Humanness ’s podcast episode with Troy Malone on Habit and Creation to Live Pain Free.)

Combine good intentions with big price tags for surgical procedures and you end up with an obvious bias toward invasive surgery.

Not only was the surgery not successful from the patient's perspective, but now the surgeon has another opportunity to perform surgery, without any evidence that a second surgery will be beneficial. This is just the next logical step from the surgical perspective. The surgeon has fixed the structural problem with surgery, and now another structure needs to be fixed to get the patient the result they want.

The initial surgeries often have little scientific evidence in their favor, but that's nothing compared to the lunacy of performing subsequent surgeries to remove scar tissue.

Cutting into the human body has a very high chance of creating scar tissue. That's a natural physiological response. So why would cutting a second time not create more scarring? I cannot find any research to support the efficacy of a revision surgery like removing scar tissue from the site of a hip replacement. Frankly, I'm dubious there's anything but high-risk-of-bias case studies written by surgeons with conflicts of interest.

In short, there is often a total mismatch of what "success" means to a patient and what it means to a surgeon.

For many surgeons, success hinges on cutting, shaving, reshaping, or replacing a given structure without infection, death, or major disfigurement.

For patients, success is measured by the ability to return to daily life and any specific athletic endeavors that they love. It's not just about surviving the surgery with minimal scarring.

When a patient hears "90 percent effective!" or "90 percent success rate!" they think they're getting an almost guaranteed ticket to the life they used to have.

See also: Can Miserable Malalignment be Fixed Quickly?

Every orthopedic surgery for joint pain comes with a risk of addiction to painkillers. Image courtesy of Halacious

The Risk of Drug Addiction with Orthopedic Surgery

Let's put aside the efficacy of joint surgeries for a moment. Say you're considering surgery for hip pain. You're being told that hip surgery is 90 percent effective, and that your surgeon is highly competent and respected by his colleagues. You aren't worried that he'll make any technical mistakes. And you're willing to put the risks of scarring and infection out of mind.

There's still a hidden risk that gets little attention.

With any invasive surgery there is a risk of becoming dependent on drugs.

For years, opioids have been prescribed with reckless abandon. They are effective at relieving pain, for a short period of time. They are also highly effective at creating physical dependency (and that's when you start to notice pain-relieving effects disappearing).

In multiple studies, researchers have found that taking opioids following surgery often leads to chronic opioid dependency, or addiction.

A 2017 study published in the journal Anesthesia & Analgesia provides a thorough overview of the challenges of prescribing pain medication in the midst of an opioid epidemic.

Regardless of whether or not patients are taking opioids prior to surgery, undergoing surgery in and of itself is a risk factor for instigating persistent and chronic opioid use after surgery. When examining the surgical population as a whole, including patients taking opioids prior to surgery, postoperative chronic opioid use ranges from 9.2-13 percent.

Becoming dependent on opioids is not something to take lightly. Chronic opioid use can lead to hyperalgesia (meaning your body feels more pain, despite increasing doses of opioids), profound constipation, mood disturbances, and respiratory depression, meaning you stop breathing and die, at high enough doses.

When people try to reduce their opioid dosage, they encounter the horrifying symptoms of withdrawal.

All of these risks come wrapped up with joint surgery of any kind. And it's only in the last few years that doctors have started safely managing opioid use.

Bioethicist Travis Rieder wrote a detailed personal account of his post-surgical experience in his book In Pain: A Bioethicist's Personal Struggle with Opioids.

He details his own struggle to break opioid dependency and the isolating and frustrating experience of finding any medical help at all for dependency (despite being well-connected with medical professionals). It's well worth a read if you want to fully grasp the risks of opioid usage.

Orthopedic Surgeons Still Have a Monopoly on Joint Pain

We already know that financial incentives point patients in the direction of orthopedic surgery when they are experiencing joint pain or immobility, but there is another problem with the way the American medical system is structured that can interfere with getting people the treatment they really need.

There is a hierarchical system at most U.S. hospitals. Ask any physical therapist (PT) about their relationships with surgeons, and you'll see the effects of the hierarchy. Unless PTs do what surgeons tell them to, they lose clients, even their livelihoods.

There's a pecking order, and people lower on the ladder don't often get to question the specialists higher up on the ladder.

So what does this have to do with musculoskeletal pain?

Pain in and around the joints historically has been the responsibility of orthopedic surgeons. Certainly, there are some other specialties that deal with joint pain (like rheumatologists and physiatrists), but the most authoritative voices in joint pain today tend to be orthopedic surgeons.

Orthopedic surgery as a field has an obvious bias to perform surgery.

If you're in a terrible motorcycle accident and shatter your femur and pelvis, you need an orthopedic surgeon to put you back together again.

Traumatic destruction needs the expertise of orthopedics!

Unfortunately, in the world of chronic joint pain, orthopedic surgeons apply the same trauma-response mentality.

You know the old saying: "If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail."

Any time joint pain is being discussed, there is one set of experts that the medical system turns to by default.

It's the surgeons. And the solution is surgery.

Who gets to question the scientific basis and the rationale of these experts?

Surely, in a free society, anyone technically can. But the loudest voices in the room—the specialists who occupy the highest rungs on the ladder (and who coincidentally generate the most revenue for their hospitals)—seem to get the final word.

Ultimately, that means the surgeons are the uncontested specialists, and that means surgery is the answer to fix chronic joint pain in the medical system.

See also: Surgery for Thoracic Outlet Syndrome – Is It Worth It?

How to Fix Your Joint Pain Without Orthopedic Surgery

What does this all mean for someone with chronic or recurring joint pain? What can we do as a society to improve the situation?

On an individual level, it's important to abide by the recommendation of many reformed orthopedic surgeons and SLOW DOWN.

Don’t rush into an orthopedic procedure simply based on the confidence of the surgeon.

Take your time and instead focus on some key steps.

- Learn how to think about your body.

- Learn how to identify muscular imbalances.

- Learn how to fix dysfunctional muscles.

Be patient and be prepared for the ups and downs of fixing your body. Find some person or some method that helps you move right and feel right over time.

Remember, in functional training, we’re always thinking about solutions through movement and muscle strength and flexibility, rather than turning to the more conventional, and often less effective, protocols for rest, ice, injections, pills, and surgery (what I call RIIPS).

In addition, on a societal level, we should demand more investigation and understanding from the medical system.

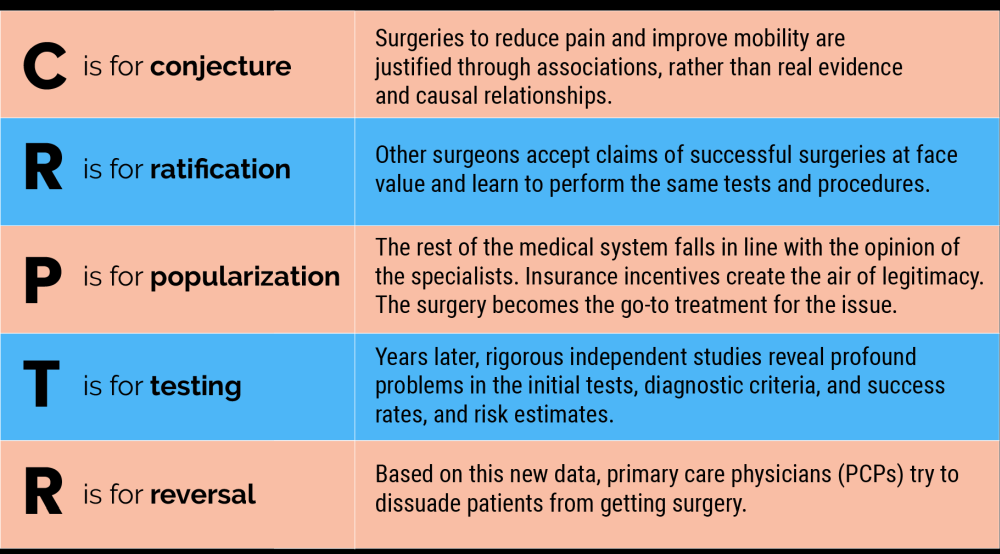

The current orthopedic model operates under a nonsensical and dangerous pattern I call CR(A)PTR.

C is for conjecture. Surgeries to reduce pain and improve mobility are justified through associations, rather than real evidence and causal relationships.

R is for ratification. Other surgeons accept claims of successful surgeries at face value and learn to perform the same tests and procedures.

And then...

P is for popularization. The rest of the medical system falls in line with the opinion of the specialists. Insurance incentives create the air of legitimacy. The surgery becomes the go-to treatment for the issue.

T is for testing. Years later, rigorous independent studies reveal profound problems in the initial tests, diagnostic criteria, success rates, and risk estimates.

R is for reversal. Based on this new data, primary care physicians (PCPs) try to dissuade patients from getting surgery.

Reversal, however, proves difficult. Patients, having already been exposed to years of highly publicized success stories, have a lot of faith in the procedures. Any attempt a PCP makes to dissuade the patient makes the PCP look like the bad guy. When a patient feels they NEED the procedure, they need only find a specialist (i.e. surgeon), who will agree with them. Many well-intentioned and well-trained surgeons continue to perform the surgeries, so a motivated patient can eventually find a surgeon to operate. Hospitals continue to collect revenue.

CRAPTR has created demand for procedures that don't work, and it's created strong financial incentives to keep dangerous quackery firmly entrenched in the medical world.

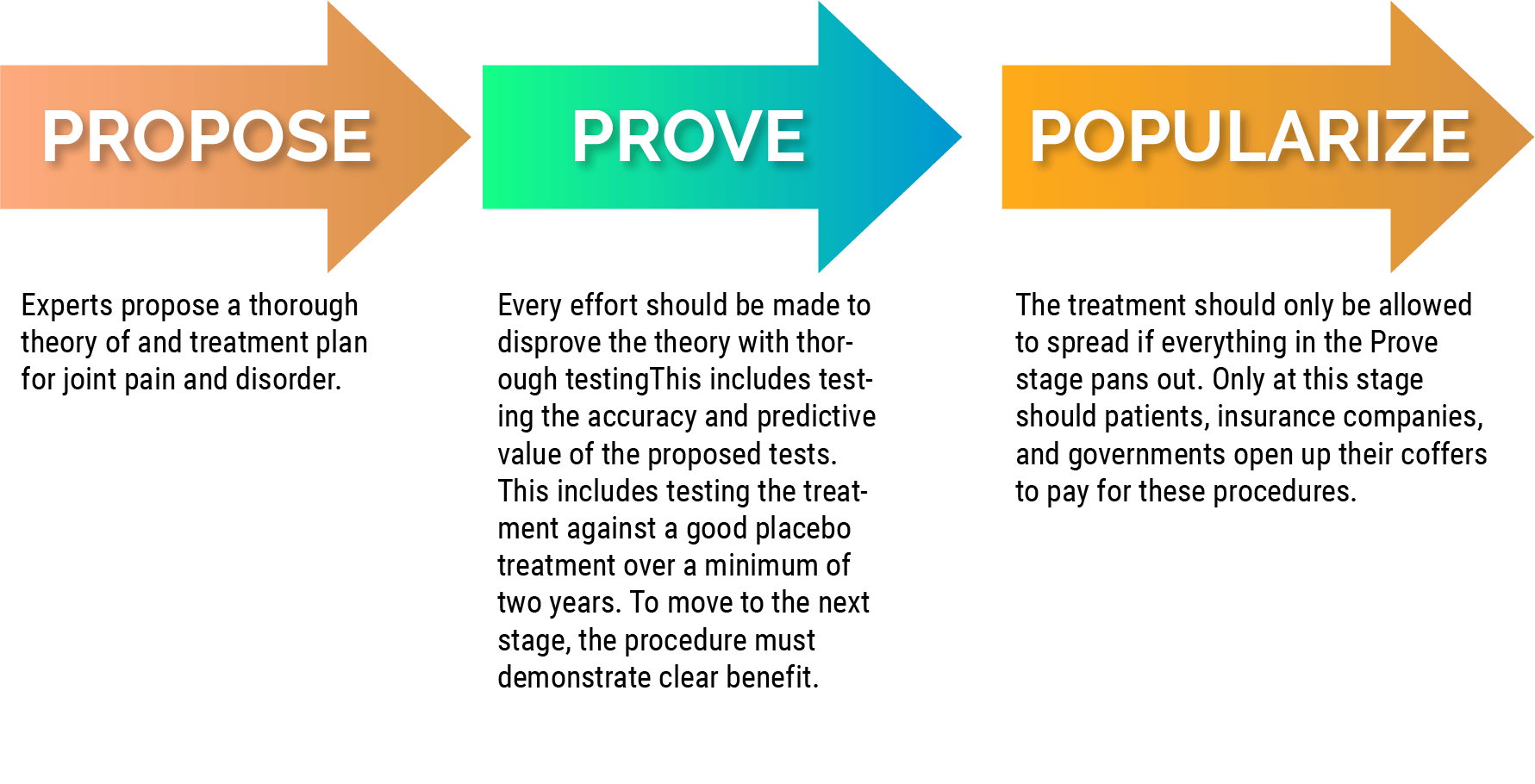

For any kind of orthopedic surgery, CRAPTR should be replaced with a Triple P approach.

Here's how Triple P works:

Propose: Experts propose a thorough theory of and treatment plan for joint pain and disorder.

Prove: Every effort should be made to disprove the theory with thorough testingThis includes testing the accuracy and predictive value of the proposed tests. This includes testing the treatment against a good placebo treatment over a minimum of two years. To move to the next stage, the procedure must demonstrate clear benefit.

Popularize: The treatment should only be allowed to spread if everything in the Prove stage pans out. Only at this stage should patients, insurance companies, and governments open up their coffers to pay for these procedures.

This Tripe P approach is the what many people believe already happens with medical procedures. It would be fantastic if this were, in fact, the truth!

See also: The Secret History of Joint Pain

Closing Thoughts on Orthopedic Surgery for Joint Pain

In this article, we've looked at the rationale behind orthopedic surgeries for joint pain. We've seen how treatments for hip, back, shoulder, and knee pain were invented by surgeons with good intentions. We've seen how rigorous scientific investigation routinely debunks orthopedic surgeries and other treatments for joint pain. We've seen how financial incentives entrench debunked treatments in the medical system and make them painfully slow to fade from popularity.

Armed with this knowledge, you can better navigate your options if you're experiencing joint pain.

Hopefully, what you've learned will delay any rush you feel to get joint surgery.

----

Ready to begin your journey out of chronic joint pain?